UC Davis Establishes Bird Flight Research Center

Unique Facility Will Image Birds of Prey in Flight to Model Uncrewed Aerial Systems

Researching how bird flight can inform aircraft design is the goal of a new center to be established at the University of California, Davis.

Christina Harvey, an assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at UC Davis, and Michelle Hawkins, a professor in the School of Veterinary Medicine and director of the California Raptor Center, are launching the bird flight research center with a nearly $3 million grant from the Department of Defense. The new center will utilize motion capture and photogrammetry — which uses photography to determine the distance between objects — technologies to image birds in flight and create 3D models of the wing shapes to inform the design and capabilities of the next generation of uncrewed aerial systems, or UAS. The center will be the first of its kind in the country.

Harvey and Hawkins anticipate that by gleaning information about how different types of birds maneuver around complex environments, they can inform the development of next-generation drones and other uncrewed aerial systems to deliver packages, detect and fight wildfires, and more.

“Michelle Hawkins and the California Raptor Center were a big reason I came to UC Davis,” said Harvey, who is trained in both zoology and engineering and joined the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering in 2022. “I can be running wind tunnel experiments [on the UC Davis campus], and then in 15 minutes, go and work with the birds directly at the CRC.”

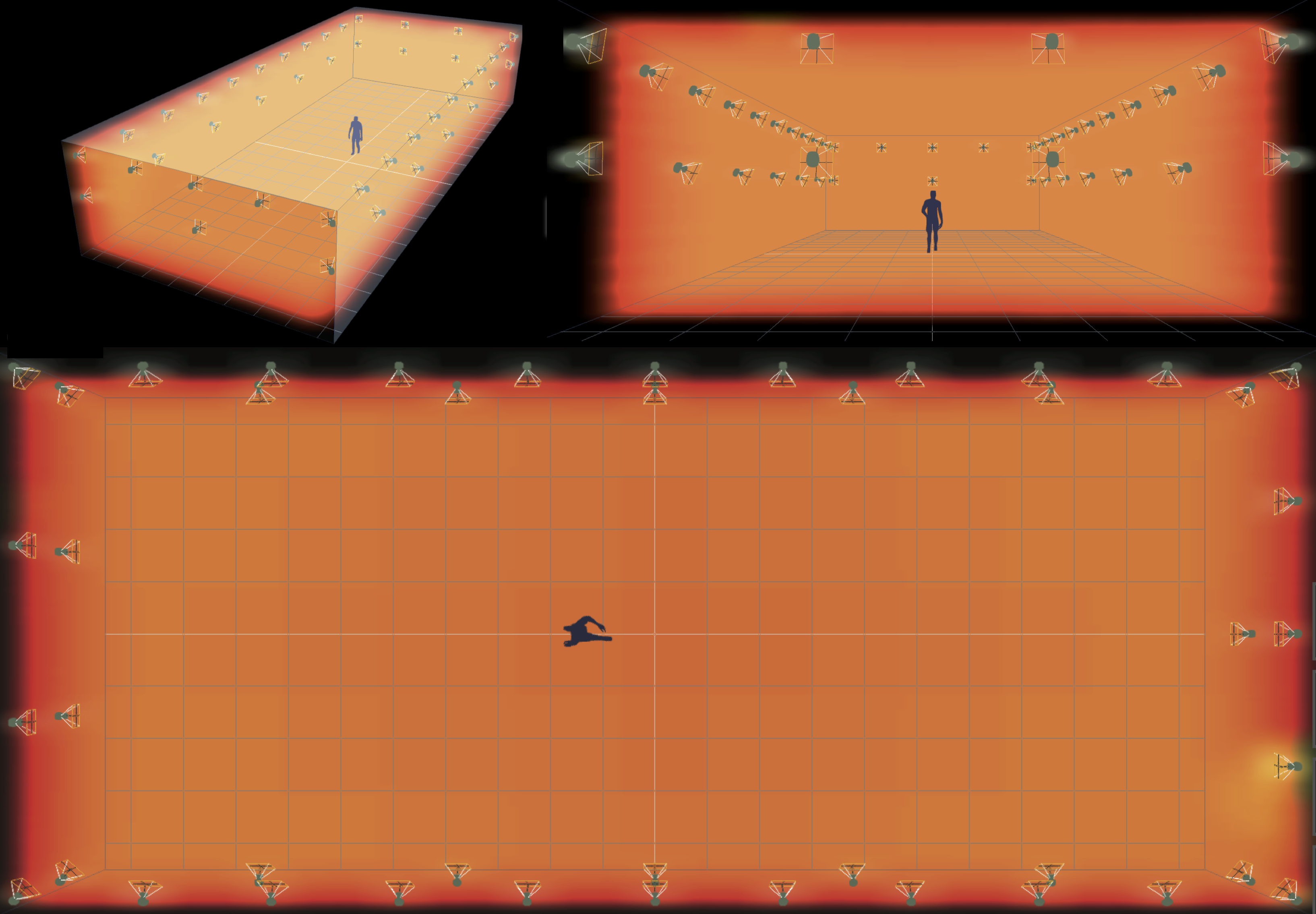

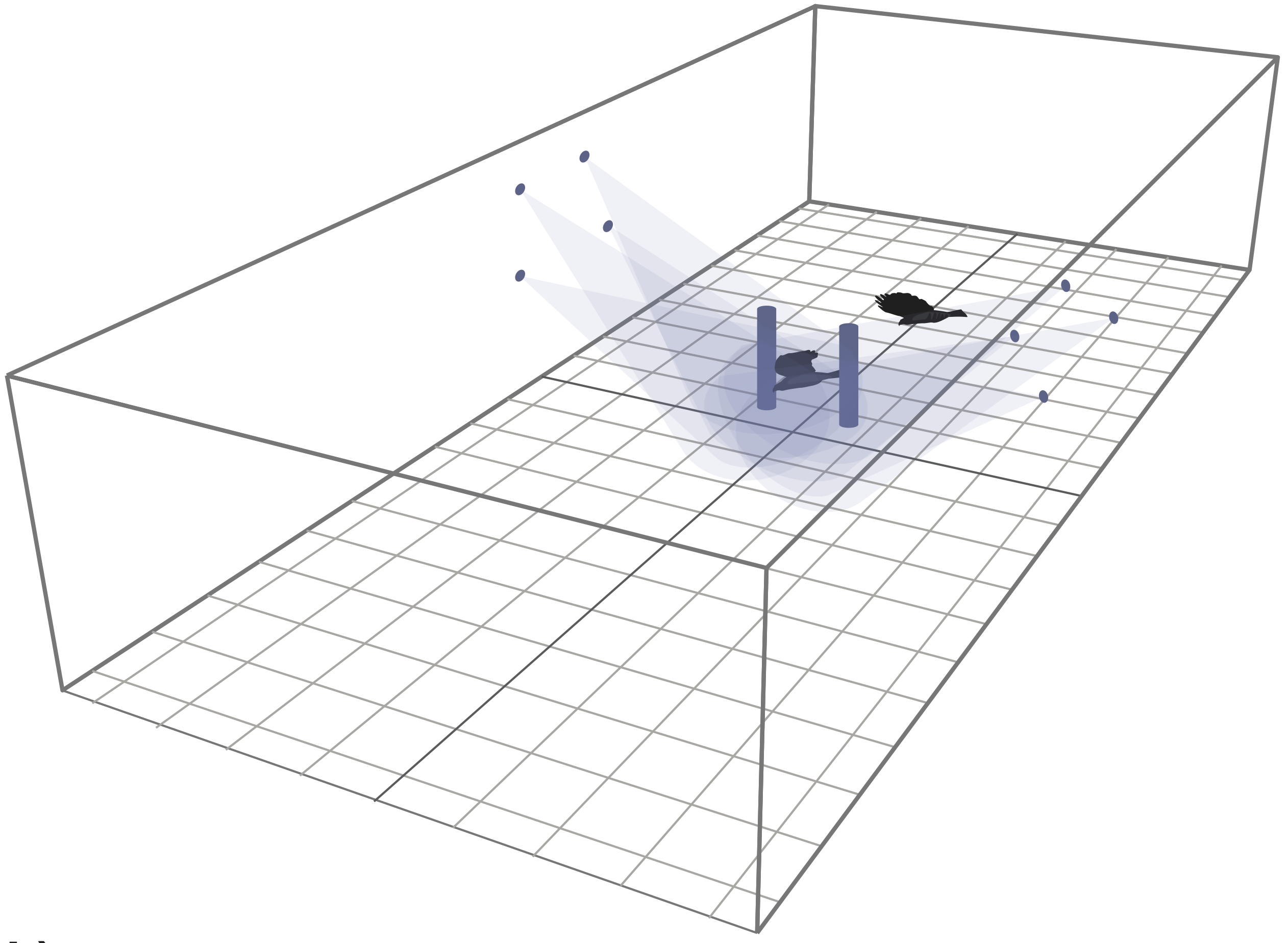

The facility is currently in the planning stages, with the goal to break ground at the raptor center this fall. It will comprise a covered, prefabricated barn that will serve as an indoor hall in which the birds can fly and maneuver. Infrared and high-speed, high-resolution cameras will be installed along the hall, which will also house holding cages, called mews, to acclimate the birds to the flight area.

Imaging birds in flight

While other groups, particularly in the U.K., have used motion capture and photogrammetry separately to perform bio-informed flight research on birds, this center will be the first to pair the two to quantify how birds react and move in complex environments.

Motion capture technology uses multiple infrared cameras to track reflective markers on the moving subject. To track the bird’s movements, markers can be placed on the bird’s wings, body and tail, as well as on obstacles to assess how a bird may maneuver around each obstacle.

However, due to the sparse placement of the markers, motion capture technology cannot be used to create detailed 3D models, which are necessary for experiments in computational fluid dynamics.

Photogrammetry, on the other hand, uses specialized algorithms to combine multiple calibrated 2D camera images to create a 3D model, but the heavy data processing load requires such high-resolution imagery that the technology has only been used to model birds in steady glides.

Harvey and her team of researchers will use motion capture to trigger the photogrammetry system to take a short burst of images when the bird enters and performs a maneuver in the cameras’ fields of view.

This will enable Harvey to create 3D models of complex wing shapes and investigate fundamental research questions, such as how birds control their dynamic systems in flight and what attributes are necessary to achieve specific maneuvers. Incorporating these birdlike attributes into aircraft design could unlock a world of potential for uncrewed aerial systems, from package delivery in remote and urban areas to wildfire surveillance.

“Remember when Jeff Bezos was out there telling everybody that drones were going to put your Amazon package on your front step? Well, that maneuverability is still not available,” Hawkins said.

Harvey added: “Think of firefighting. We don’t have an aircraft that can switch between a surveillance drone like a glider and an aircraft that can weave between trees like multi-rotors. Information we glean from this research may move us closer in that direction. This research has the potential to really impact the world.”

Benefits to the birds

Throughout her career in veterinary medicine, Hawkins hadn’t ever really considered a partnership with an aerospace engineer until Harvey requested to meet.

“When Christina got in contact with me last year, I thought, ‘You’re coming to interview, and you want to meet with me?’ It didn’t make a lot of sense, but I was absolutely curious about it,” she said. “This is so far beyond the bell curve of veterinary medicine as I knew it, and I thought I was as far out on the bell curve as there was, being a bird specialist.”

Hawkins views the new facility as a win-win for Harvey and the raptor center. Harvey will have direct access to the birds in rehabilitation who can fly, while other flight-research facilities typically outsource their birds from falconries. The birds, including turkey vultures, a peregrine falcon, a kestrel, a barn owl, kites and a red-tailed hawk named Jack, will be trained to fly down the facility’s hallway and land on a perch, getting exercise that will help with their rehabilitation and longevity.

Hawkins plans to use the imagery and modeling of the birds in flight to see where their deficits are and where to target rehabilitation efforts. She also anticipates incorporating the technology into her teaching to train the next generation of veterinarians, comparing the videos of birds in flight to the birds’ X-rays and CT scans.

“We’ll be able to do much more with the equipment available because it’s going to be so state of the art,” she said.

Laying the research foundation

Harvey already has research initiatives in the pipeline, so she and her team are fully prepared once the walls go up. Alfonso Martinez, a postdoctoral researcher in her lab, is set to begin the initial studies with some of the cameras in March to become familiar with the equipment and start collecting data. A master’s student, Francisco Jackson, has been dissecting bird cadavers to investigate wrist movements, providing possible ranges of movement, which will then be observed and juxtaposed with what the birds are doing in flight.

For Harvey, it’s the beginning of what she envisioned was possible when she first considered UC Davis.

“This partnership isn’t something that you would find anywhere else and that’s really exciting for all of us collaborating on this project.”